Para la versión en español ir a este enlace.

by Juan Pablo Laso

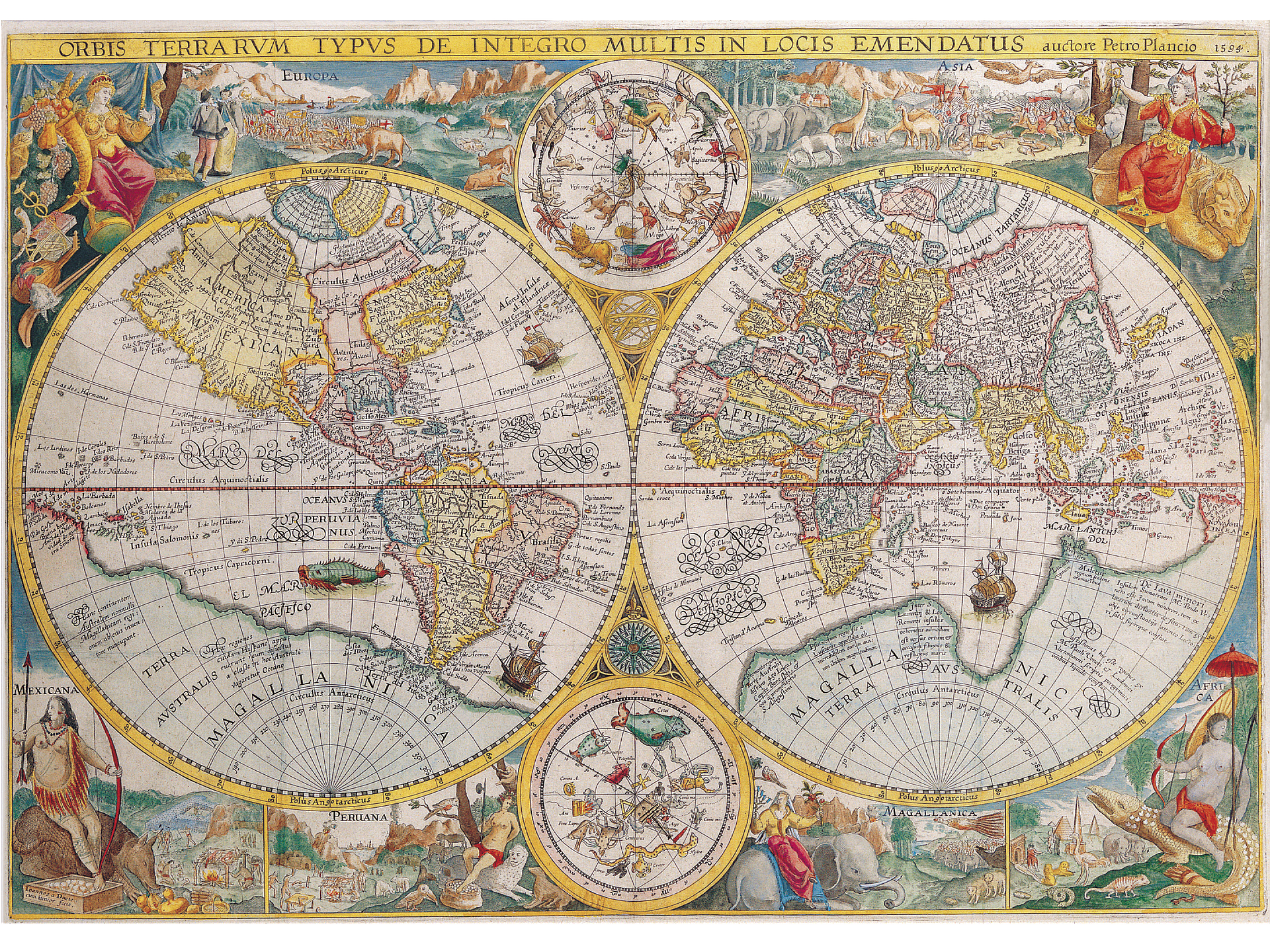

When Columbus stumbled upon the New World, its indigenous people became known as “Indians”, a misnomer of historical magnitude. Then, too, a fruit until then unknown outside of the Americas received a name that belonged to another: the pepper. To the Spaniards who tasted this fruit for the first time, its heat brought to mind the peppercorns that had been known and traded in Eurasia, and so the fruit of the Capsicum received the name of an entirely different species.

They’re better known as chiles in México, from the Nahuatl word for them, or ajíes in South America, from the Taino, and indigenous farmers have cultivated chili peppers in the Americas since antiquity. Scientists have unearthed evidence in Mexico for the domestication of Capsicum annuum, the most widespread of the five cultivated pepper species, from some 6,500 years ago. And there’s archaeological evidence that people were spicing up their meals with the wild fruit from as early as 8,000 BCE. According a paper by horticulturist W.H. Eshbaugh, early agriculturalists domesticated the plant in the Americas at least twice, independently, with another locus for the development of this species in the Amazon basin between modern-day Bolivia and Brazil. Chili peppers held great importance for pre-Columbian people as a basic component of their agriculture and trade, and after Columbus took them back to Europe on his second voyage, they became a global condiment.

While hot peppers are typically associated with other regions and cuisines – Mexican, Thai and Indian – the Amazon may be the cradle for some of the hottest peppers. The origins of Capsicum chinense (another misleading name) are the least understood, but it seems likely that the western Amazon may be the center of origin for this species. It is famous for having some of the hottest varieties in the world, like the Trinidad Scorpion Butch T pepper, indigenous to Trinidad & Tobago, or the Habanero, a variety that is widespread throughout the Americas. The Amazon, however, remains a frontier for discovery.

Travel into the Peruvian Amazon and you’ll encounter varieties such as Ají Pinguita de Mono, Ají Amarillo, Ají Plástico (similar to the Mexican Guajillo) and others at the market and growing in people’s backyards. There and in other Amazonian countries, peppers are an important part of the local economy as well as the culinary tradition. For example, in Venezuela, indigenous women are known to grow more than twenty varieties of peppers, some of which are used as medicine and some in the production of hot sauces like catara, which are then sold at market. And in Peru, the varied tastes of local markets have been found to have a powerful effect in encouraging farmers to conserve and produce a larger assortment of diverse heirloom varieties. In Colombia, the Sinchi Institute has meticulously studied the genetic diversity of the Amazonian region’s peppers. Their germplasm collection includes 377 different varieties of the six different Capsicum species that are cultivated. The sustainable use of this genetic diversity constitutes a profitable opportunity for the people of the amazon.

A new generation of Amazon explorers includes people like New York chefs Frank Castronovo and Frank Falcinelli, who, during their travel series for Vice, met with chef Pedro Miguel Schiaffino, owner of the restaurant ámaZ in Lima. Schiaffino features Amazonian ingredients in his restaurant, including particularly aromatic peppers, in an effort to define the flavors of a new gastronomy. Likewise, chef Alex Atala uses products from the Brazilian Amazon in his restaurant DOM, in Sao Paulo, ranked among the best in the world. Atala is said to be creating a new style of cuisine, but his vision goes beyond the kitchen. One of the efforts supported by Instituto ATÁ, founded by Atala, is “Pimenta Baniwa”, a blend of local capsicums grown organically with indigenous methods and made by the Baniwa women. This project is an example of how a product can be used to support a community sustainably and how production can have value beyond profit.

The pepper’s journey, from its origins in pre-Columbian rainforests all the way to its current place in gastronomy, from refined cuisine to everyday fare, embodies the better nature of a globalized world. It represents an opportunity for all of us to reexamine a ubiquitous product and look towards its origins in order to find new flavors and new ways of supporting the value chains for a more just and sustainable world.

You can find sustainable producers of chilli peppers like Proají, Mapajo, OIBI, and more on Canopy Bridge.

Recommended readings:

Researching to create a new Ají / Chili base perfume. There’s a Russian perfume like it since 2003, by Alan Bray (RIP). Looking for the know how.

Any comments on that?