Maybe it’s globalization, maybe it’s development, or perhaps digital innovations and social media; but while we are ever more connected to each other, we find ourselves more disconnected from the very things that keep us alive. Amidst our computers, phones and other devices, with so much information, I find it staggering that I need to be reminded of my connection to Earth: the origin of the water I use, how the air I breathe has come to be, where my food comes from.

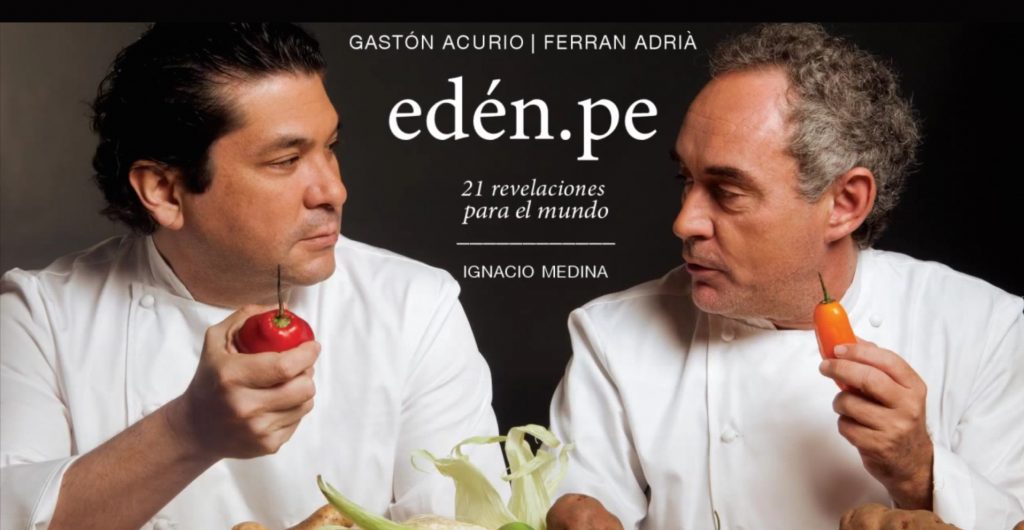

Yet, I do need reminders, reminders that spur action, change and everyday consciousness. For me, Eden.pe is one of these. Eden.pe is a remarkable book, a journey to the origins of food in Peru by Ignacio Medina that ties together cuisine, farmers and the Earth. Like its name, it reminds us of the paradise we live in, the good fortune we have of experiencing connection, and its magical flavours. It connects us directly to the origins of our food, and through it, to the soil and the hands that tend it, to its journey to our plate, and the creativity of the hands that turn something as simple as a potato into a soul-shaking experience.

The book is a journey: The story of twenty-one Peruvian products told individually, starting with the name and photograph of who grew it, where and how. Next is a recipe featuring the product: a completely new creation by one of the twenty-one most creative and renowned chefs in the world invited to participate.

It’s difficult to really understand the significance of a potato without climbing Monte Azul, or visiting the eateries that surround villages like Tres de Mayo, right there, in Kishki. You take the path that leaves the main road and you start to climb until you get close to 3700 meters above sea level…Fatigue and lack of oxygen are slowly forgotten as the landscape expands beneath you and the monumental horizon that surrounds you widens. (21)

Although about Peru, the spirit of the stories in Eden.pe are relevant to realities found around the world, where the often-unknown suppliers of our pantry are the pillars of our paradise. Continuing the publication of a series of works by gastronomic journalist Ignacio Medina, we present another of his remarkable writings hoping it can also spark in you what is needed to shorten the distance between your life and its ingredients.

With every step you take in Peru, you find a producer that reveals your own disgrace; the depths of the chasm that separates you; the distance between the fundamental role they play as pillars of the country’s pantry and the half-truth – that’s always a half-lie – that surrounds your life; the unjust disregard of the people that do more for Peruvian cuisine than all of us together would ever be willing to do. They have the key to Eden. Our Eden. (23)

For the Spanish version click here. Para la versión en español ir a este enlace.

Karina Bautista

From Eden.pe

by Ignacio Medina

We’ll be sharing excerpts from the book, with special thanks to Ignacio and the publisher, Phaidon Press, in hopes of sparking connections to the origins of some very special foods throughout the region. The following passage tells of one of the most characteristic ingredients of Peruvian cuisine and one of the farmers that grows it.

Rocoto Peppers

We find rocoto in the Andean crops, at altitudes that can reach 3500 meters, taking advantage of its resistance to the lower temperatures, although we can also find it in the central jungle, where it has found a habitat that favors the development of larger, fleshier fruits, with an ever growing demand. Built around it is one of the millenary axes that have fueled Peruvians’ ancient culinary habits […] So it was with the Incas and before that with the Nazca, Moche, Chimu and Paracas cultures. Five thousand years of barter featuring this usually red pepper –though there are also green , yellow and orange varieties – of varying sizes, which exhibits the highest level of spicy heat amidst the most emblematic chilis in the market.

The rocoto is known by the Quechua as luqutu or rukutu, a much older name than its botanical nomenclature: Capsicum pubescens. (328)

Santos Pineda Batallanos

On the sixth of November in 2011, shortly after noon, we found Eden. It was a strange day. A taxi, while it was still dark, to the Lima airport, the flight to Cusco, three hours by car towards Abancay, a dirt road that leads into the mountains, followed by a narrow, uneven footpath ascending the hills to bring us, thirty minutes later, to the home of Santos Pineda and Vicenta Huamanñahui, where we cross the threshold of paradise. We’ve arrived at Granja Bello Paraíso. This must be the closest to Eden that I can imagine. In barely a hectare of land surrounding the house, I find more than a hundred species of fruits, vegetables, flowers, herbs and medicinal plants, combined in search of the perfect balance. At the highest point, three trout ponds and beehives near the viewpoint overlooking the immensity of the valley, with Abancay at the lowest point […] Santos and Vicenta have another two hectares under cultivation and fourteen more covered with forest, and a few cows. They grow no more than they can consume and what they can sell in the markets, Wednesdays and Sundays in Abancay. Vicenta is in charge of that. Very early in the morning, she loads twenty kilos of products and takes the road to the city. Today is Sunday and she returns by three having sold everything. The rocoto peppers sold for 30 céntimos apiece; the price can reach 50 céntimos when it´s scarce. The community of Llañucancha – meaning thin and toasted in Quechua – adjectives tied to memories of the old landowner (hacendado) in lands where only cancha (corn) was planted – is made up of eighty families and some 480 neighbors. There are still twenty families that suffer from illiteracy, but everything has changed since they arrived. Every family in Llañucancha is energized by a vital project; Santos Pineda and Vicenta Huamanñahui want to develop a community tourism center. Perhaps because of this one of their sons is studying cooking. The other three are studying agronomy at university. In this part of paradise they raise frogs and lizards to fight the Insects that attack the plants. Meat is rarely part of the diet here; only for special celebrations. The trout that they offered me in this part of Eden was small, with white, flavorful flesh. It’s the best trout I recall eating, ever.

The forests of the hills of Llañucancha disappeared the day the old hacendado gave the order to cut them down to make tools from their wood. All this land has been dedicated since then to corn, until the community decided to recover the forest. Their labor is almost complete and they are working now to substitute eucalyptus for one of the more than eighty native species, like unca, chuyllor, ta’sta or maki maki. (330)

Currently, Granja Bello Paraíso can only offer its products in local markets. However, if you are in Peru, in the Cuzco region, you can visit this garden of Eden through its community tourism initiative. Check out their profile on Canopy Bridge to learn more.

If you are looking for sustainable producers of chili peppers in the region, make sure to visit the profile of Proaji, or in the case of Andean products, see Candela Peru.

2 thoughts on “The Hottest Chillies in Eden”