by Juan Pablo Laso

In Noli, a small comune in Liguria, Italy, Thomas Jefferson reports that you’ll find “a miserable tavern, but they can give you good fish viz. sardines, fresh anchovies, [etc.] and probably strawberries; perhaps too Ortolans.” In Rozzano, a comune in Milan, he recommends that you “ask for Mascarponi, a rich and excellent kind of curd, and enquire how it is made.” In Koblenz, “call for Moselle wine”, and in Avignon “taste the vin blanc de Monsieur de Rochegude, resembling Madeira somewhat.” But, of course, it is in Bordeaux where you’ll find “the owners of the best vineyards.”

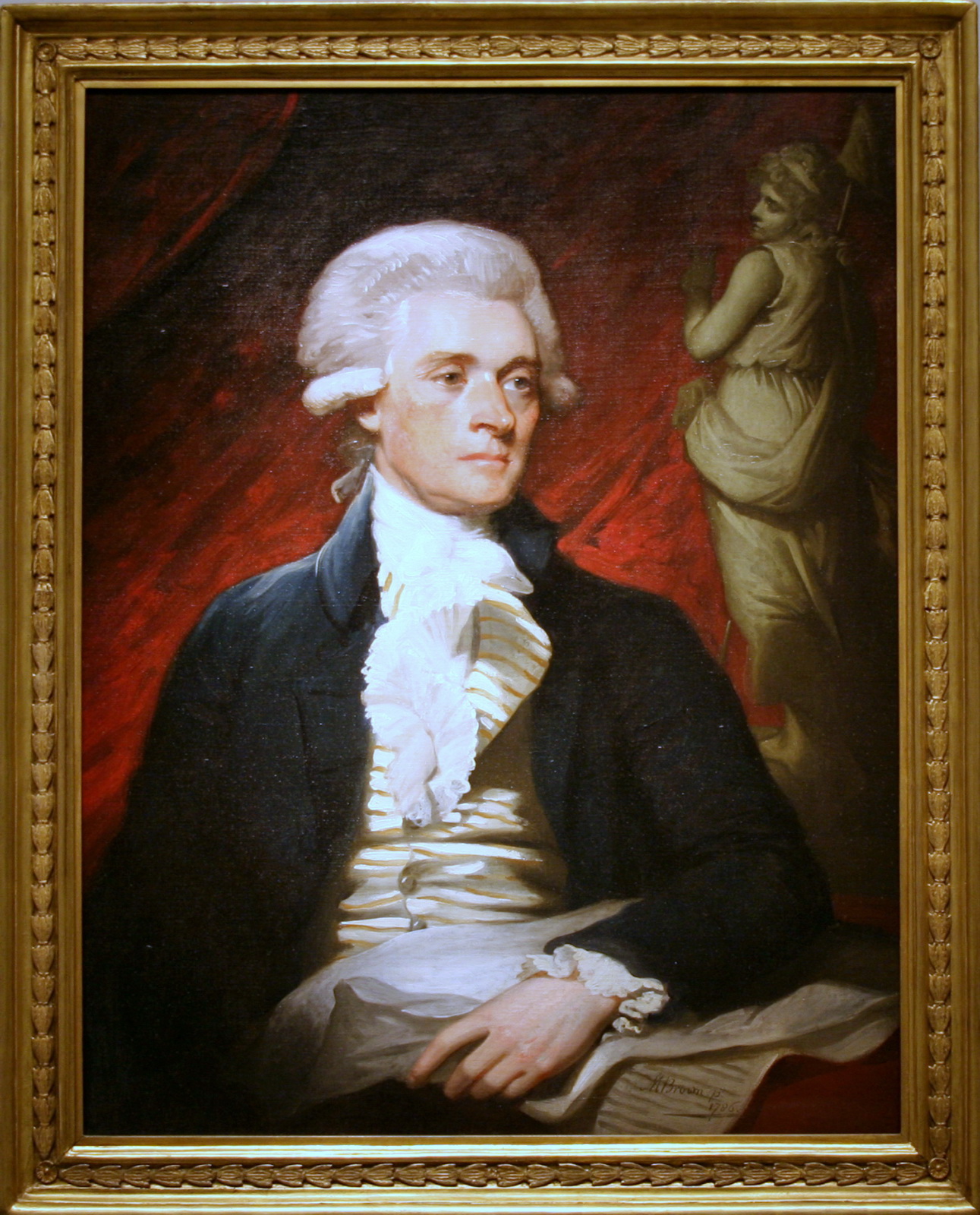

Thomas Jefferson: Founding father of the United States, Secretary of State, Vice President, President, and… culinary traveler?

While serving as Ambassador to France, Jefferson traveled Europe extensively. Among his papers, you’ll find “Hints to Americans Travelling in Europe”, a set of notes that predates TripAdvisor by over 200 years, but serves a similar purpose. His “Hints” are peppered with encounters with the local food and wine, which were an essential part of his three month long journey. Jefferson sought to discover Europe deeply, somewhat in the way that a backpacker today would seek to know a place, off the beaten path, where the genuine flavors of the land reside. In a letter to the Marquis de Lafayette, Jefferson extols “the first olive fields of Pierrelate” and “the orangeries of Hieres”, and advises that to get to know his own country, he should “ferret the people out of their hovels […], look into their kettles, eat their bread…” There was cultural and political insight to be gained from this immersion in the French countryside, from truly getting to know what the people eat, what they drink and how they live.

The UNWTO Global Report on Food Tourism cites evidence that “over a third of tourist spending is devoted to food.” Food is inextricably present in any travel experience, but gastronomic tourism is an emergent phenomenon that emphasizes getting to know the world above all through the food and drink of its people. As travelers today seek more and more to have an authentic and enriching experience, food and drink are central to a location’s ability to showcase its culture and identity.

In this same report Iñaki Gaztelumendi, a consultant with over twenty years experience in the tourism industry, states that “tourism today is paradoxical” because “it simultaneously generates processes of globalization and enhanced appreciation of local resources”. A region’s products and its gastronomy are an important part of its intangible heritage, and they are necessarily the basis for the tourism that they may attract. Many of these products will face the prospect of extinction due to the homogenizing pressure from globalization on culture, or what may be known as McDonaldization (per sociologist George Ritzer). At the same time, it is this globalized world that offers unparalleled opportunities for the sort of cultural experiences that can lead to a better understanding between people. Gastronomic tourism entails opening a local economy and making its products attractive to the world while defending the culture that gave rise to a culinary tradition.

If you watch Anthony Bourdain try a tamal at La Puerta Falsa, a small restaurant in La Candelaria (one of Bogota’s traditional neighborhoods), you can better understand how it is that food and culture are inextricably linked. He is in the company of Héctor Abad, one of the best writers of his generation, with whom he unpacks not only the food before them, but the history around them. Wherever he goes, food serves as an essential window to the country and the people. In his latest episode of Parts Unknown, Bourdain traveled to Beirut, a city where, after being caught in the middle of a war in 2006, he’d realized “there were realities beyond what was on my plate, and those realities almost inevitably informed what was — or was not — for dinner.”

For modern travelers, gastronomic tourism represents an opportunity to do as Jefferson or Bourdain have done: to seek culture at its origins. Countries like Peru and Mexico are taking a page from traditional destinations like France, Spain and Italy, and defining their identity by means of their gastronomy, with the hopes of drawing in more tourism. Take Mistura, for example: since 2008, Lima has hosted a food festival celebrating Peruvian cuisine in September. It was started by a group of chefs led by Gastón Acurio who have sought to make Peru a premier destination for food. Last year, attendance rose to 600,000 people, according to NPR, and this initiative has expanded to include other Latin American cuisines under a project called Salsa Para el Mundo. In a similarly significant effort, the Secretaría de Turismo de México has catalogued and mapped the country’s gastronomic routes on a dedicated website. You can’t go wrong if you want to explore Mexico’s cuisine, declared by UNESCO to be a part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage.

Countries everywhere can look towards their gastronomy to find value and a way to open up to the world. You are what you eat, after all, and perhaps it is traveling to eat what the world has to offer that we will be able to know what our fellow human beings brew in their kettles and what they talk about over a hot drink, and to better understand our culture at the source.

This article is the first in a series about gastronomy. Canopy Bridge seeks to innovate in the ways that we can support sustainable producers from around the world. Gastronomic tourism offers an opportunity for our products, their origins and their stories to become known. Later this year, you will find us at Latitud Cero, a food festival in Quito that is a part of Salsa Para el Mundo project.

Anthony Bourdain

Parts Unknown

[clear]