Versión en español aquí

Versão em português aqui

Article by: Jacob Olander, Gabriela Albuja, Kevin Moull, Chris Meyer, Juliana Splendore and Karina Bautista

Introduction

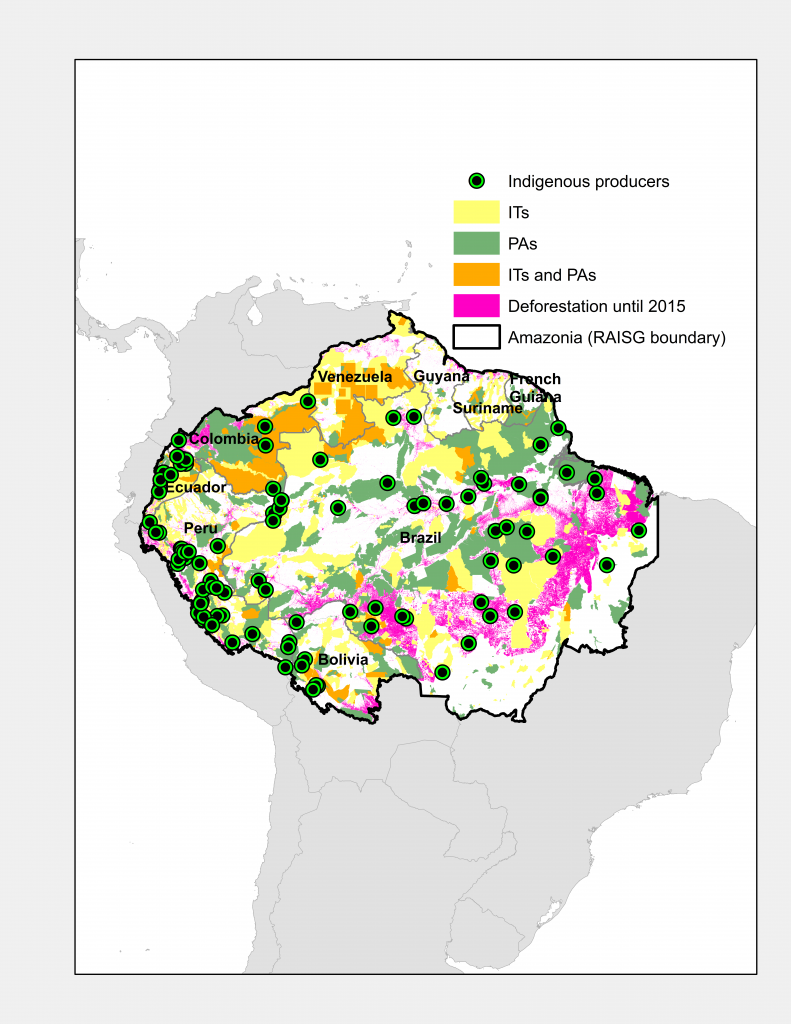

When properly supported, indigenous communities can make significant contributions to rainforest conservation. Legally recognized indigenous territories (ITs) cover over one fifth of the Amazon and, because they tend to conserve intact forests, account for an even larger percentage of forest biomass and carbon storage (Walker et al. 2014). Deforestation rates have been shown to be far lower within indigenous territories than in unprotected lands (Blackman et al. 2017; Busch y Ferretti-Gallon 2017), with a recent study, indicating that Amazon deforestation rates were more than six times lower in indigenous territories (RAISG et al. 2017).

Since the mid-1980s important progress has been made in recognizing and demarcating indigenous lands throughout the Amazon. While significant areas of traditional indigenous territories remain to be recognized (some 20 million hectares in Peru alone, according to the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest – AIDESEP), securing land rights has been a fundamental achievement for enabling cultural survival and forest conservation (Ding et al. 2106).

Despite legal recognition, many indigenous territories continue to face existential threats fueled by economic drivers. With land legally secured many indigenous communities continue to confront pressures from illegal activities, or confront a devil’s bargain: opening up their lands and forests to mining, ranching and timber interests in order to generate income. A key next-generation challenge after securing territorial rights is ensuring economic sufficiency and resilience, building working indigenous economies that reconcile the need for income, traditional cultural values, and the sustainable use of natural resources. Many indigenous communities, organizations and peoples are rising to this challenge, creating enterprises, projects and networks.

A review of data in an on-line database Ecodecision has compiled in partnership with the Environmental Defense Fund, Forest Trends and the Coordinadora de Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica – COICA, shows the enormous scope for synergies between strengthening indigenous territories, conserving protected areas (PAs) and investing in indigenous enterprises.

Indigenous enterprises and overlap with conservation areas

We drew on a database of indigenous economic enterprises and projects available on-line and populated with data provided by users and by researchers at Ecodecision and the Environmental Defense Fund since 2014. The database includes 126 indigenous enterprises and projects in the Amazon, encompassing 5 countries and more than 100 different indigenous peoples or ethnic groups. See Appendix 1 for a description of this database and this analysis.

Of this total we were able to confirm 83 (66%) as being located within the boundaries or buffer zones of 33 protected areas and 60 legally recognized indigenous territories, covering approximately 105 million hectares.

For the remaining enterprises for which verification of the relationship to conservation areas was not possible, there is a high probability that most are also geographically related to protected areas or indigenous territories. Based on available location data and proximity analysis, 19 additional enterprises are associated with at least 5 additional protected areas and 12 indigenous territories, covering an additional 1.3 million hectares. Insufficient information was available for the remaining 24 initiatives to confirm the relationship with conservation areas and indigenous territories.

The actual number of indigenous enterprises contributing to conservation in the Amazon is certainly far larger than the current inventory in our data set, given the constantly evolving nature of economic activities and the difficulties in communicating and confirming activities across remote areas.

Of course it would be simplistic to assume that economic activities of indigenous peoples near conservation areas invariably contribute to conservation. Some activities may not be sustainable. However, it is worth noting that of these initiatives, 25 were confirmed as involved in some type of voluntary certification system (e.g. Forest Stewardship Council, Rainforest Alliance and others).

Emerging successes

A small but significant portion of the initiatives identified have achieved significant economic activity and organizational success, and represent opportunities to invest in further strengthening these enterprises and expanding their positive impacts. These include cases like:

- A number of indigenous organizations producing high-quality native cacao or chocolate for international markets, including Kemito Ene (Ashaninka, Peru), Kallari and Wiñak (Kichwa, Ecuador), AMWAE (Huaoarani women, Ecuador) and ARCASY (Yacaré, Bolivia);

- The Yawanawa, Paiter-Surui and the Waimiri Atroari peoples of Brazil, and PATS Peru, developing sophisticated handicrafts for export;

- Indigenous fruit and non-timber forest product initiatives like the Sateré-Mawé people of Brazil, who sell certified organic guaraná (fruit used in energy drinks) to Europe, the Eca-Amarakaeri indigenous organization in Peru who harvest Brazil nuts from their communal forest reserve, and the ASMUCOTAR women´s association, from the Colombian Amazon, with over 10 years of work producing and processing camu camu fruit into frozen pulp.

- Reforestation and forestry operations including Peru´s Shipibo Conibo indigenous organization, Promacer, one of the only indigenous enterprises producing legal certified timber in the Amazon, as well as the Rede de Sementes do Xingu-Araguaia, a network of indigenous peoples and traditional rural communities that sells reforestation seeds of native species to land owners in Mato Grosso State (Brazil).

Challenges and room for growth

The fact that the overwhelming majority of indigenous enterprises and economic initiatives occur near and within conservation areas indicates an important opportunity for investing jointly in the sustainability of indigenous peoples and biodiversity conservation. Strengthening these enterprises can contribute directly to the sustainability of conservation areas, reinforcing the capacity of indigenous peoples to act as bulwarks against deforestation.

And the need for support continues to be significant. Our data and interviews also indicate that more than 80% of these initiatives are struggling to become or stay viable, due among other reasons to difficulties in reaching buyers and markets, challenges in securing access to finance, and limitations in creating and sustaining institutional and administrative capacity.

With major commitments to national-level REDD+ programs in the Amazon countries, there is a significant and largely unrealized potential to invest and leverage these funds into self-sustaining economic activities lead by indigenous peoples themselves that can contribute to the conservation of millions of hectares of forest.

References

Blackman, Allen, Leonardo Corral, Eirivelthon Santos Lima, y Gregory P. Asner. 2017. “Titling Indigenous Communities Protects Forests in the Peruvian Amazon”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (16): 4123–28. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1603290114.

Busch, Jonah, y Kalifi Ferretti-Gallon. 2017. “What Drives Deforestation and What Stops It? A Meta-Analysis”. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 11 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rew013.

Ding, Helen, Peter G. Veit, Allen Blackman, Erin Gray, Katie Reytar, Juan Carlos Altamirano, y Benjamin Hodgdon. 2106. “CLIMATE BENEFITS, TENURE COSTS The Economic Case For Securing Indigenous Land Rights in the Amazon”. World Resources Institute. http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/Climate_Benefits_Tenure_Costs.pdf.

RAISG, Ecociencia, Gaia Amazonas, Instituto Socioambiental, Instituto del Bien Común, Woods Hole Research Center, Enviornmental Defense Fund, y COICA. 2017. “Amazonian Indigenous Peoples Territories and Their Forests Related to Climate Change: Analyses and Policy Options”. RAISG. http://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/indigenous-territories-barrier-to-deforestation.pdf.

Walker, Wayne, Alessandro Baccini, Stephan Schwartzman, Sandra Ríos, María A. Oliveira-Miranda, Cicero Augusto, Milton Romero Ruiz, et al. 2014. “Forest Carbon in Amazonia: The Unrecognized Contribution of Indigenous Territories and Protected Natural Areas”. Carbon Management 5 (5–6): 479–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/17583004.2014.990680.

Appendix: Background and Methods

Indigenous Atlas

In order to map indigenous enterprises, EcoDecision, COICA, Forest Trends, and the Environmental Defense Fund created an open-access online platform – Indigenous Atlas . Here, users and institutions added basic information as well as approximate geographical locations (pins) of indigenous producers in Latin America. Basic information fields in the database include:

- Name of enterprise

- Indigenous/ethnic group

- Products

- Description of enterprise (where one can include: certifications, supporting agencies, number of producers, etc.)

- Producer contact name

- Producer e-mail

- Producer telephone

- Producer website

From this data set, we selected the 126 initiatives that were located inside the Amazon boundaries, as defined by the Amazonian Network of Georeferenced Socioenvironmental Information – RAISG.

Confirmed relationship between indigenous enterprises and protected areas or indigenous territories

RAISG databases were also used to define the boundaries of protected areas and indigenous territories in the Amazon region.

We then made an effort to identify the protected areas and indigenous territories corresponding to or in the surrounding areas of indigenous enterprises. Out of the 126 indigenous initiatives, we were able to confirm that 83 had relationships to PAs or ITs. To identify these 83 enterprises we:

- Verified through direct contact with or self-reporting by representatives of indigenous producers that their initiative was within or in the buffer zone of a protected area or indigenous territory.

- In cases where we were unable to receive additional direct confirmation, overlap with conservation areas was confirmed by:

- Review of secondary information online and published sources indicating association with protected areas and indigenous territories.

- Location of user-generated pins inside protected areas (PA) or indigenous territories (IT) and consistency with data in enterprise description [1].

Unconfirmed relationship between indigenous enterprises and protected areas or indigenous territories

For the rest of the initiatives for which we could not directly confirm their relation to PAs or ITs, we performed a proximity analysis.

This analysis was done by comparing the self-reported pins on the map with the PAs and ITs from the RAISG databases. We then identified enterprises and organizations with locations <5 kilometers from the boundaries of PAs and ITs, yielding another 19 experiences.

Acknowledgements

This project and information was prepared as part of the Accelerating Inclusion and Mitigating Emissions (AIME) project supported by the United States Agency for International Development. AIME is a 5-year project of the Forest-Based Livelihoods Consortium (FBL), a partnership of nine environmental and indigenous organizations led by Forest Trends, and including Alianza Mesoamerican de Pueblos y Bosques, the Coordinadora de Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica (COICA), Earth Innovation Institute, Ecodecision, Environmental Defense Fund, Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM), Metareilá, and Prisma.

This publication is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

[1] The nature and limitations of the geographic data set should be noted; pins and location data are user-generated and of variable precision. They were meant primarily as a user-interface tool to identify and “put indigenous producers on the map,” rather than describing the exact boundaries of enterprise activities.

Additional photo credits: Kallari

Recommended readings:

Chankuap Foundation: A Cosmetics Factory In The Amazon Forest

5 Amazonian oil producers that taught me how to appreciate oils

Fish-farming paiche: a Cofan alternative to preserve the forest

Much more than a label: Origens Brasil shows you the people behind the products

Peru’s Amarakaeri People Learn To Have Their Nuts And Sell Them, Too